2015 was a pretty good year for comics, but not so good it couldn't be improved. That's why, for our end of year competition, we asked y'all to gild that lily like motherfuckers.

It seemed like a good idea at the time: you'd pitch us comics, we'd talk about our favourites, and we'd send one of you the real, actual comics we liked the most from 2015. We figured it would be easy; we'd get about five submissions, right?

Ha ha. Nope.

Boom. 101 hot steaming pitches.

Clarrie “The Clarrie we talk about when we talk about Clarrie” Maguire

Title: Catching Gnats

Genre: Comedy Drama

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Bored teens work in Torquay during the summer holidays to pay for their surfing dreams and/or cider and weed.

Title: The Lady With The Braid

Genre: Black Comedy

Length: ongoing

Pitch: 1980. Two newly qualified Northern Irish nurses share a London flat. After an eventful weekend involving an abusive boyfriend and an unrelated home invasion, they become serial killers.

Title: Hillside

Genre: Teen horror

Length: miniseries

Pitch: It's in the woods, and it *will* fuck you.

Title: Vanilla Extract

Genre: heist romp

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Lesbian crimers in the 24th century! Neon colours! Feminist ideals! The comic for ladies to read after Bitch Planet in order that they not kill themselves!

Title: Breaking Free

Genre: non-fiction

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: Non-fiction exploration/history of left wing activism in eighties and early nineties UK, both in reality and pop culture. Interspersed with chapters from that mental Tintin bootleg 'Breaking Free' that used to be passed out where Tintin and Captain Haddock end up leading a people's revolution.

Title: Dinosaur Planet

Genre: sf adventure comedy

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: All ages licensed comic of MJ Hibbett's concept album 'Dinosaur Planet'. Bright colours. Mad art.

Title: Jakey Work

Genre: supernatural light drama

Length: ?

Pitch: A low key supernatural drama about an ageing Cunning Man in rural England between the wars.

Title: A Book Of Days

Genre: fantasy/magical realism

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: During a year with the worst harvest in living memory a widowed farmer in eighteenth century England cares for, and eventually marries, an amnesiac stranger who has been rescued from near drowning in a pond on his land. (SPOILER: she gives birth to summer in the end and dies because she was mythological all along, that was why there wasn't really a summer the year before - when she had no memory - and the harvest was so bad FUCK YOU THIS IS SOME LYRICAL BITTERSWEET SHIT)

Title: Batter bread, orange shit, and sweet potato cock

Genre: diary comic (fictionalised memoir?)

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: Cooking, self worth and women's relationship with the media are explored in this story of a fat woman from an eighteen year old with an eating disorder to a thirty year old HAES activist who will fucking cut you.

Title: 5pm - 10pm inclusive

Genre: horror

Length: one shot

Pitch: A kind of rotting Ewok looking monster kills a dude. No dialogue. Told entirely through full page panels of the back of his house, including three windows, as viewed through the back door of the house opposite.

Title: Daisy Dick Lew

Genre: fantasy

Length: ongoing

Pitch: A kid moves to a village in rural Wales. All manner of mythic shennanegoats are going down. The weird old dude running the corner shop post-office and his housebound altzeimery mum are Mordred and Morgause/Morgan,trapped together by obligation and immortality. Two of the dickheadiest kids in his year at school might be Arthur and Merlin reborn. His mum is being an arse, and frankly puberty was already quite stressful.

Title: Night Visitor

Genre: horror

Length: one shot

Pitch: An increasingly housebound pensioner who has lived their life under the shadow of a draining supernatural entity discovers that they have a terminal illness and resolves to take a final revenge on it.

Title: Dogwet

Genre: fantasy

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: in a fantasy world inhabited by huge, unknowing, lovecraftian creatures, a derelict fisherman and a mute child scrape out survival in a cave in a cliff-face.

Title: But I'm All Right Now

Genre: non-fiction

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: at last, a non-shit biography of Hattie Jacques.

Title: The Alphabet Game

Genre: mystery

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Lesley Mison solves crime while managing schizophrenia.

Title: Take A Penny

Genre: memoir

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: A comic about the years I worked full time in a Bristol corner shop under a manager who wrote Buddhist poetry about giving 110% and got dumped by his girlfriend on Mount Fuji after proposing.

Title: Information Dance

Genre: drama

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: An action adventure comic from the point of view of a bee.

Title: Nearer and nearer crept the ghastly thing

Genre: fantasy horror

Length: series arc in an ongoing

Pitch: London 1954. Reality fractured in 1944. In 1947, the effects were contained within a slowly expanding but largely stable area in central London and all sentient supernatural creatures were given automatic amnesty and citizenship. Patricia Dartnell works as a home visitor for the recently overhauled welfare system, children have started to go missing and she wants to know why.

Title: Sheep, Sheep, Crocodile

Genre: horror

Length: ongoing

Pitch: It's the sixties, and everyone's involved in drugs and cults and psychedelic esoterica. But is this druggy cult about to go really bad? Well, you read the genre description.

Title: Mrs Locke

Genre: crime

Length: ongoing

Pitch: 1920: The young 'widow' Locke - formerly one of the first female detective constables in England* - has a gift for private investigation, and a complicated series of mutual debts to the government that requires her silence regarding the famous, and still living, father of her in fact entirely illegitimate child.

Title: Ghost-Fuck

Genre: porn

Length: ongoing

Pitch: People fuck, or are fucked by, ghosts.

Title: Young Fibonacci

Genre: adventure

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Tesla and Lovecraft better look out! In this exciting steam punk adventure, it's Fibonacci who's reimagined as a rough and tumble adventurer fighting largely spiral based crime in twelfth century Italy.

Title: Sonic OC

Genre: drama

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Dave Sonic, an unemployed bricklayer from Chorlton, inherits a house in glamorous Orange County California. With wacky results.

Title: Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

Genre: drama

Length: miniseries

Pitch: Dave Arise is an inner city cop in a far future New York where anything can happen! Also there are mech suits.

Title: Cakes And Ale

Genre: drama

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: Samantha's grandfather, Dave Cakes, is about to lose his beloved pub and she must step in to help. Also, she is a teenage girl who is coming to terms with her bittersweet lesbian crush over the course of a summer so rogger loves it and says that I am the best and I have won and gives me all the prizes.

Title: Deadpan

Genre: crime

Length: ongoing

Pitch: A meek criminal autopsy specialist tries to solve crime and keep their sanity while living with their abusive grandmother and developmentally disabled brother. Gripping if depressing.

Title: The Winter Gardens

Genre: drama

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: A former cook, butler and maid in a disbanded wealthy household run a guest house in an English seaside town in the immediate aftermath of the first world war.

Title: Run, Lizzie Biscuit, Run Right Now

Genre: adventure

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Lizzie Biscuit has a problem. She doesn't know what it is, but the people pursuing her certainly seem to have a grasp on it.

Title: Hog

Genre: non-fiction

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: biography of Sequoyah the inventor of the Cherokee syllabary.

Title: Chicken, Two Ways.

Genre: comedy

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: A broad adaption of La Cage Aux Folles set in Hastings. Laurence 'Larry' Bald is trying to arrange a meal between his fiancee's Tory politician parents and his adoptive parents Rob and Andy Moriarty-Bald, who are about to retire from running their bar restaurant The Bird In Hand. Unknown to Laurence, before his birth the bar catered to a *very* different scene and was central to a messy political sex scandal. A docu-drama of which is being filmed there this very weekend. LAFFS AND IMPORTANT LESSONS ABOUT FAMILY/PARENTING ENSUE.

Title: Bleed

Genre: drama, suspense

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: Following a messy divorce and back in the town where he went to university, Chris White hooks back up with the remains of his old gaming group. But is one of them really a killer? Or are his suspicions a reaction to being back in a social circle that insularity and geek social fallacies has stagnated into something unhealthy over the last twenty years?

Title: Yan Tan Tethera

Genre: folklore, history, anthology

Length: ongoing but composed of one shots and mini-series

Pitch: Folk tales and weird history from the North of England. 'we're flittin', the Barghest, 'my own sel', Jinny Greenteeth, the Pendle witches etc.

Title: Ii

Genre: drama, light supernatural adventure

Length: ongoing

Pitch: There is a secret society of thousands, perpetuated by intermarriage and careful training. Dedicated to the protection and assistance of The Chosen One. Last month, she told them to get fucked. What happens when your messiah resigns? When your life, the lives of your ancestors for a thousand years, no longer has purpose? Ii explores this. "Imagine Buffy, I Claudius and Anthony Burgess had a baby" said Pretend Comics Forum.

Title: This Truth Came Borne

Genre: horror

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: An elderly couple are trapped in their house by silent creatures made of bone.

Title: Maputo

Genre: SF

Length: ongoing

Pitch: A woman and her granddaughter travel post-industrial flooded future Medway by boat, trading and interacting with the inhabitants. Maputo is the name of the boat.

Title: Basjo Pangles

Genre: all ages adventure

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Basjo Pangles is a brightly coloured cartoon bear. Davies is a highly strung owl who owns a pneumatic drill. They are highwaymen in an adventure filled green wood.

Title: Nightbus

Genre: light comedy drama

Length: series of one shots in an ongoing.

Pitch: In a pub in a village, Karen and the rest of the regulars drink with her best friend Nightbus. They do a meat raffle, have a band in, raise money for charity, go on a booze cruise, one regular buys a motorbike. That kind of thing. Basically kind of a low key English 'Cheers' but one of the characters (Nightbus) is a storybook giant and they never acknowledge this. Watercolour art. THIS IS NOT ONE OF THE JOKE ENTRIES. I HAVE WRTTEN SO MANY SCRIPTS FOR THIS.

Title: Kancho

Genre: supernatural

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: 1948. A young Japanese widow prepares to remarry and move to the US, with her young son. He begins to act out, but is it the normal stresses of a small child adjusting to change or is it spirit possession?

Title: It Turns Out That I Can Only Write Folk Horror?

Genre: Folk Horror

Length: ongoing

Pitch: A woman decides to combine a fun writing exercise with some mild cyber-bullying only to discover that about ninety percent of her ideas are some variation of the kind of 'Children Of The Stones' stuff that ITV used to do a lot of in the late seventies.

Title: Batman

Genre: Batman

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Batman.

Title: Heartbeat, But With Vampires.

Genre: Adventure, Horror, Scenic Views Of The North York Moors, Manga

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Oh no! Wicksy has got bitten by Dracula, and now it's up to Mr Derek and Alkie Selwyn Froggitt to stop him from spreading his corruption through the Yorkshire countryside of 1965-ish like an unstoppable late Victorian metaphor for venereal disease.

Title: Ultimate Call The Midwife

Genre: action adventure

Length: ongoing

Pitch: The characters from popular BBC program for nans 'Call the midwife' are given a updated, continuity free, reboot in this accessible jumping on point for new readers.

Title: The Saga Of The Victors

Genre: horror

Length: mini-series

Pitch: Literally just a photocopy of Skywald 's 'The Saga Of The Victims' with Richard Wilson's head stuck over all the faces.

Title: Mabigdogian

Genre: fantasy

Length: ongoing

Pitch: The Mabinogion, but with big dogs.

Title: Sail Away, my darling doll.

Genre: poem, drama,

Length: short

Pitch: Drawn in the style of willow pattern plate. The women of a small sailing village in C18 live their everyday lives in the absence of men.

Title: Captain Space

Genre: sf low key adventure light drama

Length: graphic novel

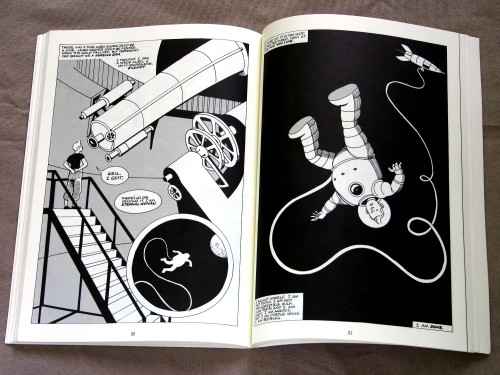

Pitch: Captain Space, an Ovaltine era style intergalactic adventurer secretly crash lands in the woods behind a realistically written Essex council estate in 1991 and moves into an empty house. He has an alien dog, and a robot butler and robot aunt. He also almost certainly has some degree of combat based PTSD, a possibility which he is unaware/unwilling to entertain. Drawn in the style of Herge.

Title: Riddles Wisely Expounded

Genre: myth, fantasy, folklore, anthology

Length: one shots and mini-series within an ongoing

Pitch: Adaptions of stories from the Child Ballads.

Title: Gandaberunda

Genre: drama

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: A wealthy Bengali tea farming family in Northern India struggle with the differences between the UK influenced culture of the elder generation and the US focussed aspirations of the young. Both seeing the other as polluted by colonialism and themselves as the 'real' India.

Title: Skull Balloon

Genre: anthology

Length: short

Pitch: One page dialogue free stories in a six by six grid.

Title: You'll Never Believe Number 14

Genre: disaster, sf

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: End of the world narrative shown through clickbait listicles.

Title: Withered Heart

Genre: horror

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: A loose adaption of 'The Residence at Whitminster' by M.R. James. Dr Oldys and his young wife move into a house with a dark past and a fly infestation.

Title: Uranium Rock

Genre: comedy drama

Length: ongoing

Pitch: In the mid-fifties, with the sexual revolution still a glimmer in society's eye and the threat of nuclear war seeming very real indeed, a group of teens cope with life by planning and executing flying saucer hoaxes in the New Mexico desert and doing some half-hearted prospecting.

Title: Tired

Genre: tired

Length: ongoing

Pitch: so fucking tired

Title: Excerpt from A Teenage Opera

Genre: comedy drama

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Join Dave Opera as he starts at a new school in a new town. Where his mum is the headteacher!

Title: Steam

Genre: superhero

Length: ongoing

Pitch: A young thief in a youth detention centre discovers that he can transform into a cloud of vapour at will and decides to use his powers to become a hero.

Title: Home Virtues

Genre: non-fiction, porn, comedy

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: History of that weird period in the 1860s where the letters page of 'Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine' (of Mrs Beeton fame) was almost exclusively a hang out for hairy palmed BDSM enthusiasts.

Title: Dr Orangutang

Genre: children's

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: Victorian London. Dr Orangutang is a medical doctor, who is an orangutang. He's got a little top hat and mutton chops and that. It's very adorable.

Title: The Kitten's Tea And Croquet Party

Genre: non-fiction

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: Biography of Walter Potter, and history of the Walter Potter museum.

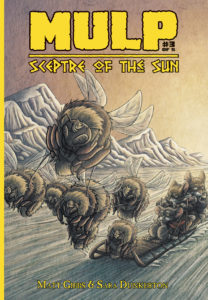

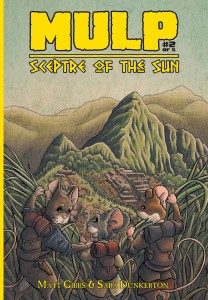

Title: Mulch

Genre: superhero

Length: ongoing

Pitch: When Kayleigh Tenson was eleven, she was a bystander during a battle between magical superheroes and supervillians. She was killed, which was sad. But she got better, which was rad. Nine years later she finds out that if she can magically rot things, and furthermore if she doesn't do it every day she'll die again. Which is very much a mixed bag.

Title: Hammer And Sickle

Genre: action adventure

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Lenin hunts vampires.

Title: Adam

Genre: supernatural drama

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: A young boy living with his mentally ill mother in the fens during the late forties begins to worry that he may be the antichrist.

Title: Kit Kat Ate A Rat

Genre: crime, adventure

Length: ongoing

Pitch: Two bored dancing girls in twenties London become an unlikely crimefighting duo after foiling a blackmailer who threatened their peers.

Title: Hunter’s Chicken

Genre: folktale,

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: Art is photos of Fuzzy Felt collages. A motherless boy whose father has gone to market prevents various supernatural creatures from invading the house and doing him various harms.

Title: Cold Cream

Genre: comedy drama, horror

Length: graphic novel

Pitch: The adventures of Montague Ince, Victorian actor and necrophilliac.

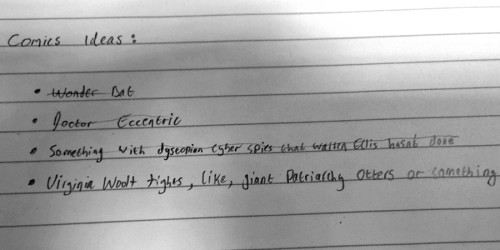

Oliver

‘The Boy With The Arachnid Heart’.

It’s the heart-warming tale of a young lad, Keith, who discovers that he has poisonous spiders instead of blood. Whenever he is hurt small but ferocious spiders rush from the wound and attack everything in his immediate vicinity. Death is not certain from their bite but profound suffering is. Keith is profoundly arachnophobic. A sinister government agency wants to turn him into an assassin but Keith is more concerned with whether or not girls will be repulsed by his gruesome, spidery blood and the worry that his semen might actually just be spiders eggs as well.

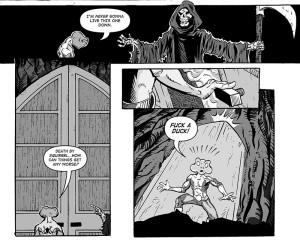

‘Death and Other Small Disappointments’.

A woman’s organs become self-aware and have to solve the mystery of why they all feel so awful all the time. It turn’s out that their host is drinking herself to death. Her organs must decide whether or not they want to try and save her because if they do they themselves will cease to be self-aware and effectively die. Do they want to live in the crumbling body of a dying woman or die in the body of a woman who might just live.

‘The Lear Effect’.

The world is falling apart because God has become senile and divided his creation up among the archangels Gabriel and Michael, and the devil Lucifer. As they vie for control reality itself begins to fall apart causing people to be confronted by the gods of alien races on the other side of the universe. A scientist and a priest must team up to try and stop the world ending by creating the world’s first laboratory grown deity.

Innesbrook and Outen

An off-beat supernatural detective story. A husband and wife team solve crimes with the help of their unusual psychic powers. Innesbrook can psychometrically get information about objects used in crimes but only by cramming them into his anus. Outen meanwhile can gather information about a victim's past but only by defecating in the cadaver's mouth. They fight against both the forces of crime and the outraged relatives of murder victims.

John

Title: Nic Cage is Superman!

Main Character: Nic Cage.

Pitch: Nic Cage *actually is* Superman.

Dave will love it.

Title: Flavious the baer!

Main Character: Flavious.

Pitch: It writes itself.

Hoggy

Fool House

A depressing, refusing-to-come-of-age story about a manchild who won some comics in a populer and intelligent podcast bingo competition and the half-arsed depths he will sink to in order to win again. Self published via photocopying on the office printer when no-one's watching.

Warren Ellis' Ian Fleming's James Bond 007 in KRAMPUSSY

Uncle Warren downs a bottle of cooking sherry and pens this IP crossover when Her Majesty's Secret Service sends their foulest agent up against the sinister foreign seasonal avatar who threatens the UK's peace of mind. Bond triumphs in a 300 page long sequence of lovemaking techniques that are legally not allowed to be depicted in the UK.

Rogger's Laminated Typography Manual

this isn't actually a comic but the kerning is amazing and it's wipe clean.

Al

Shatner

Portly ageing emoter William Shatner is losing his faculties and believes he's character's he's played in the past. Hilarity ensues, but tinged by the sadness of seeing someone succumb to dementia. So it's not

all that fun then.

Goat-goat

A goat with the power to transform into a goat. Slitty eyed arsehole.

Hungover-girl

Perplexed by the world, a woman wanders through town, diligently using pedestrian crossings even though the road is closed to cars.

Alpaca

a reflective, existential comic. An Alpaca stands in a field, chewing

Daily Mail Man

Runs around with his pants on his head, shouting racist epithets at the gays, leering at twelve year old girls.

Corbyn

a genial Bernard Cribbens impersonator becomes leader of the Oppposition. Hijinks ensue!

Tony

philanthropic millionaire keeps getting mistaken for a blood thirsty warmomgering grasping arsehole

Toto

small dog from Kansas starts wildly successful soft rock band fond of terrible metaphors

Rogger: [censored]

"I'm Dave": Like "I'm Dave Gorman", except Dave (any) goes round finding

people called Dave. There are many.

Piano Man: A gin-based accident sees Billy Joel combined with his piano.

He fights crime

Hester

Title: Hester!

Main character: Hester!

Pitch: It's about Hester.

Rogger

Walking Styx

On or about December 1910, whatever might have once passed for a god or meaningful cosmology of any kind went out for a smoke, hasn't been seen since. While this was undeniably important, and a good many people, both living and dead cared a great deal, Alfred Wainwright and Nikolaus Pevsner thought it sounded like a nice chance to get out in the fresh air. Now they lead a series of coach and walking tours around a derelict afterlife. Like Dante's Inferno via One Foot In the Grave, and with a good deal more bickering about Edmund Burke than you'd expect from either.

Bloomsbury Jam

London, 1938. The Bloomsbury Set play roller derby against the Mitford Sisters and chums. It's violent, lurid, a wee bit dykey, and historically spurious at best, but is their end of season grudge match just a toff dust-up on wheels, or is something more sinister being decided about the future of the British political establishment?

Dreadnaught

In 1910 a bunch of posh pricks in just *incredibly* racist fancy dress managed to trick their way aboard the HMS Dreadnaught, pride of the Royal Navy. This much is established historical fact. Less well known is the fact that they promptly nicked it and took to the high seas. So what exactly did happen? And just what might you get up to if your crew included a shapeshifting socialite, an ambiguously psychic Freudian analyst, a painter/philosopher/incompetent wizard, an author haunted by spectral raves who sing perfect songs of the future in deeply imperfect ancient greek, and an annoying little man possessed by the budget-trickster-god genius loci of a minor public school.

Hungry like the Woolf

No, don't worry - even I have standards.

Giles

It's a Sad Comic that alternates between scenes of the bittersweet childhood and comic-yet-melancholy old age of a sarcastic former caped vigilante from the British midlands, where it gradually becomes clear that it's taking place in a virtual reality sustained by malfunctioning supercomputers on a dying Earth billions of years in the future.

The plot is, I don't know, some sort of ironic time loop probably.

I think that covers about everything.

Chris

Title: Being Kieron Gillen

Genre: Kieron Gillen

Length: 3x6

Pitch: Kieron Gillen writes a comic about a comic book writer who is a thinly disguised avatar for Kieron Gillen who is writing a comic about a comic book writer who writes really really terrible puns. (just kidding Kieron, love you really)

Title: Rob Liefeld's Feet

Genre: Body horror

Length: Ongoing

Pitch: All the feet Rob Liefeld has obscured/hidden/just plain failed to draw in every comic he's ever done since, like, 1980-whatever.

Title: Captain DC

Genre: Superhero or something I guess

Length: Too long

Pitch: Like Captain Marvel but with totally tone deaf gender politics, maybe she gets her superpowers whenever she's on her period or something? That would be totally empowering for women, right? Also tits.

Title: The Disruptive Adventures of Valley Techbro Boy

Genre: Hacker News

Length: Until this fucking bubble bursts; with any luck some time early next year

Pitch: It's Like Uber But For Comics. Uber the horrible company, I know Uber is already a comic.

Title: Sexy Smiley's People: The Comic Book

Genre: Espionage, Ben Whishaw

Length: About 4 minutes and then Rogger loses interest and feels a bit dirty

Pitch: That TV series as a comic book. Special wipe-clean print-stock.

Title: Being Chip Zdarsky

Genre(s): Sex, Horror, Horrible sex, Canada

Length: Too long

Pitch: No oh god no oh Christ please just make it stop

Title: Netflix and Kill

Genre: Slasher, revenge fantasy

Length: 6 issues

Pitch: Jobless millenials run out of things to watch on Netflix and go on a killing spree, murdering the baby-boomers who fucked everything up for them. Published on Tumblr or Snapchat or something I guess.

Title: Netflix and Quill

Genre: Media commentary

Length: 6 issues

Pitch: Everyone's favourite Elizabethan playwright Billy Shakesbro offers his views and hot-takes on the latest shows on the streaming internet video service

Title: Netflix and Gil

Genre: Crime/detective procedural

Length: 6 issues

Pitch: The revolution will not be televised, but it will be streamed right to your front room when Gil Scott-Heron and his trusty sidekick Netflix get on the streets to... look, this seemed like a good idea when I started ok

Title: Netflix and Krill

Genre: Fish somehow

Length: 6 issues

Pitch: It's about some tiny sea creatures who watch things on a streaming video service maybe? I'll be honest I haven't thought this one through

Title: Grant Morrison's Adventure Time

Genre: Fucked-up acid trip

Length: 1 issue, or the whole of time and space

Pitch: Honestly not that different from a normal issue of Adventure Time tbh except maybe with more murder and drugs and fucking

Title: Warren Ellis and the Mysterious Neurological Event

Genre: Autobio

Length: Ongoing

Pitch: In which everything is FINE and NOTHING BAD HAPPENS and Weird Uncle Warren gets to write more comics and not die or anything, OKAY?