To say that with Battling Boy Paul Pope owes a debt to Jack Kirby would be to understate things drastically. By Pope’s own account the seed of the idea that eventually became this book was when an attempt to pitch DC Comics a revival of Kirby’s 1970s teen-in-a-post-apocalyptic-world, Kamandi, was met with the response that DC didn’t make comics for kids any more, but “45-year-olds”.

It’s hardly surprising then that the influence of Jack Kirby is all over this book, from a floating technological fortress filled with gods, to the look of the characters (Battling Boy’s dad looks like the halfway point between the Silver Age Thor and Kirby’s Fourth World character Orion, another character looks suspiciously like Big Barda). The style is all his own though, Pope’s manga-infused frenetic inks as distinctive as ever.

For a self-styled “comics destroyer”, Pope is nothing if not a contrarian, setting out thoughtfully to create a kid-friendly comic that captures the joy of coming across fragments of these grand mythologies as a child - a character here, a huge, never-to-be-explained machine there. It stops at tribute though - Pope’s own inventiveness doesn’t allow it to descend into magpied pieces of someone else’s work.

Arcopolis is a city under siege from monsters. The city’s champion, Haggard West, and his daughter Aurora protect the city as best they can, but when Haggard is killed Arcopolis is left broadly defenseless. Meanwhile, Battling Boy’s parents must select somewhere for him to prove himself as a hero - something traditional for his people when they are turning 13. And so a city full of monsters has a teenage demigod - dressed like a normal kid, save for a huge red cape - thrown into it, and Battling Boy needs to find his place in a world he doesn’t understand. It’s rich stuff, but it’s hardly the “chosen one” mythology so prevalent in modern children’s literature.

Battling Boy’s main concern is living up to his parents’ legacy (they’re a lot more impressive than they are supportive, it has to be said), and his unworldliness leading to the adults of Arcopolis (or more realistically, the government - this is Paul Pope, after all) trying to exploit him as both their protector and something they can take credit for. It’s far more coming-of-age story than epic sweep, and the story stops somewhat abruptly - to be picked up again in a follow-up volume and at least one spin-off, The Rise of Aurora West (to be drawn by the fantastic David Rubin - hopefully this will lead to an English translation of his mythological / superhero comic, Le héros). There’s also a preview comic, The Death of Haggard West, but all of that is included in this volume, so it’s not necessary to track it down separately to read or enjoy Battling Boy.

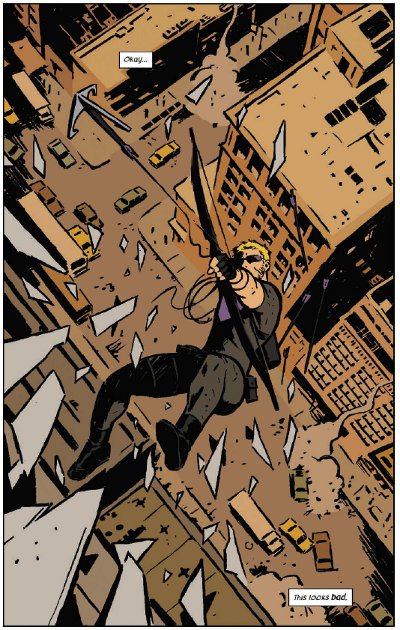

I've praised Pope's artwork before, and it's just as good as ever in Battling Boy. His line seems a little finer and neater than usual - this could just be the reproduction; the book is quite small. Whatever the cause, it suits the bright and clear world of Arcopolis. In the monster underworld, more of the inky squiggles and sound as texture that have been prevalent in his work creep in - and it works, given these scenes a slightly grubbier, more B-movie feel (a chainsaw in a guitar case helps with that) next to the much more straightforward overworld.

Special praise should be given to Hilary Sycamore’s colouring. Pope’s work to my mind usually looks better in black and white - his freehand inks don’t really suit colouring in the standard line / ink / colour process. Just look at something like Batman: Year 100 for an example of where colouring genuinely detracts from his art (or compare the recoloured reissue of The One-Trick Rip-Off to the original black and white version). In Battling Boy, though, Sycamore has chosen a limited, mostly-flat palette that works well with Pope’s kinetic linework. That the backgrounds are less packed with detail than is often the case with his work helps. I also didn't realise the book was lettered digitally until seeing the credits page - digital lettering usually makes my brain itch, so I'm chalking that up as impressive.

There's a trailer that gives a surprisingly decent feel for the comic here:

[embed]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xK2AR9z4j5Y[/embed]

Battling Boy is excellent and, much as it feels strange to recommend Paul Pope for kids, I wholeheartedly do. Adults too, and in particular Silver Age aficionados. First: Second, who published this, are still on track to publish another of his kid-friendly works in the near future - the long-hibernating THB. When it finally reappears, I'd recommend that too.