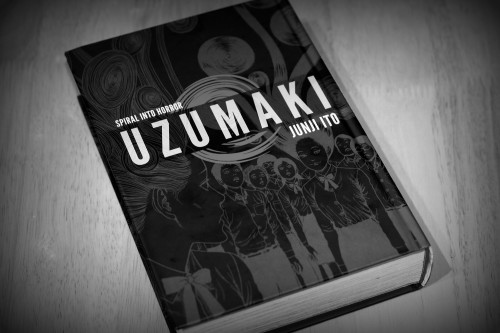

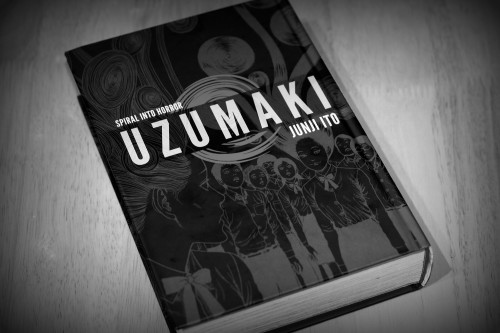

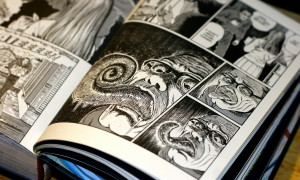

Uzumaki (spiral) was on our reading list for the horror comics podcast, and for a putative future edition on Manga. It's a collection of short but connected horror stories by Junji Ito, centring on the town of Kurouzu-cho, which has been "contaminated with spirals".

It's been available in English, on and off, since 2001, and I remember leafing through the early Viz Media editions back when I was shifting comics and manga for a loose approximation of a living. The 2013 "3-in-1 Deluxe Edition" collects all the stories for the first time, and is a genuinely handsome piece of publishing.

That cover and binding are where the nice things about Uzumaki start and stop. This is a creepingly unpleasant book - a taut and unsettling one-volume lesson in how comparatively simple words and pictures can be deployed to make you want to sleep with the lights on.

Uzumaki is seen largely through the eyes of Kirie Goshima and Shuichi Saito, a kind of schoolgirl everyman, and her increasingly reclusive boyfriend. They see the spiral infestation wind its way through Kurouzu-cho, consuming and distorting their friends, families, and eventually the entire town.

It's a quiet thing as it starts, and Kirie's gentle, almost wide-eyed observation makes the reading experience oddly immediate. Indeed, the gentler first two chapters that introduce her and Shuichi are some of the most effective. It begins with the uncanny in a fraught suburbia, coiling through body horror, the supernatural, and gradually unwinding to something of a far larger scope as the book progresses. At its liveliest, it's caper-like, intriguing rather than frightening, as though Haruki Murakami found himself drafted in to write episodes of Round the Twist. At its gentlest, you're afraid to turn the page.

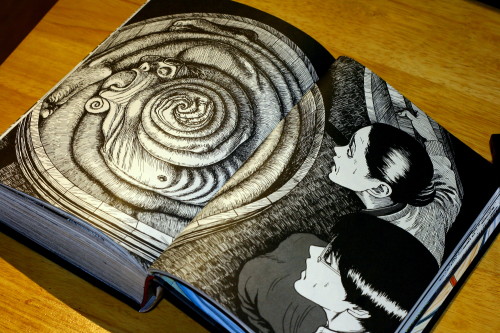

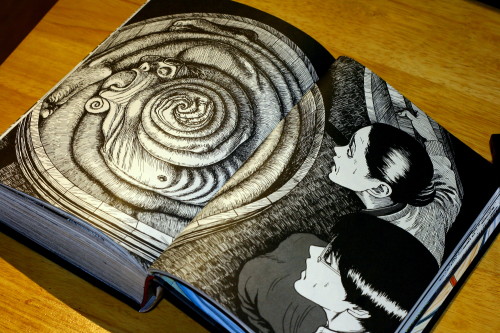

The first story begins by making Kurouzu-cho gently oppressive. The opening pages are simple, with Kirie telling us about her school, and encountering a small whirlwind on the way to meet Shuichi from the station. She finds Shuichi's father staring, entranced by a spiralling snail shell, the single-panel view of it drawn more vividly and in tighter detail than any other so far. It's an odd interlude that establishes the motif, and unnerves just slightly.

The first story begins by making Kurouzu-cho gently oppressive. The opening pages are simple, with Kirie telling us about her school, and encountering a small whirlwind on the way to meet Shuichi from the station. She finds Shuichi's father staring, entranced by a spiralling snail shell, the single-panel view of it drawn more vividly and in tighter detail than any other so far. It's an odd interlude that establishes the motif, and unnerves just slightly.

All the while, Kurouzu-cho presses down. The shading for the sky seems low and close, and the sea around it too dense. Shuichi points to this explicitly as he explains his growing unease in the town. All the while, Kirie maintains her light, almost naive narrative voice. It has that "and then this happened" note of childish, unaffected description. We're reading the "what I did on my holidays" piece from a horror movie suburbia.

That quality of unselfconsciously introducing the next thing that happened lets Uzumski sneak the gently creepy (and downright horrible) under our noses without much cue that it's coming. Shuichi's father, for instance, becomes increasingly erratic. It's described mildly, in conversation and glimpses, concerning rather than frightening - the old man is clearly becoming odd and detached.

Then we turn the page.

Jump scares are tricky in comics; you can't control reading behaviour, after all. But well-deployed full-page surprises can work, and Uzumaki uses them sparingly to great effect. The first isn't really a scare, but it prefigures this story's grotesque climax. It's just Shuichi's father in his study, surrounded by his collection of spiral objects.

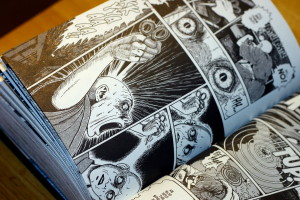

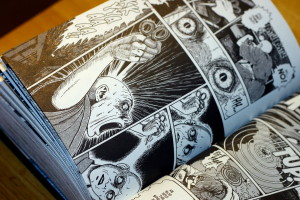

But it's such a break from the panel flow. The borders are thicker, the detail, like the snail shell, is rendered more meticulously, and it introduces the aggressive crosshatching that gives Uzumaki so much of its atmosphere. At its most severe, the clean outline is replaced entirely by dense, curved hatching that builds shapes and figures from itchy layers of semicircles.

The first time it's used for a character is also the first hint of anything fully supernatural in Kurouzu-cho, and next to the previous pages' relatively Manga-conventional, simply lined character design, it's a shock.

The first time it's used for a character is also the first hint of anything fully supernatural in Kurouzu-cho, and next to the previous pages' relatively Manga-conventional, simply lined character design, it's a shock.

The pure density of the pen strokes makes Shuichi's father somehow monstrous, and the close focus on his eyeballs, as he rotates them in a spiral, is unpleasantly physically intimate.

In a few pages time, his spiral obsession has distorted him physically. Almost choking, he unfurls a huge, grotesque, tongue, coiled into a spiral. The dense hatching draws in again, and the focus is tight on his face. Looking away is not an option.

Then this:

It's not nice.

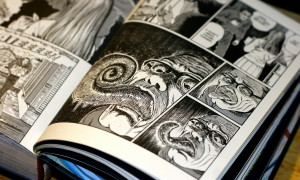

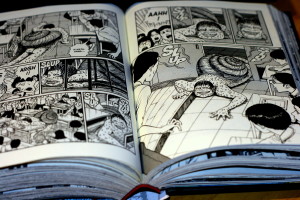

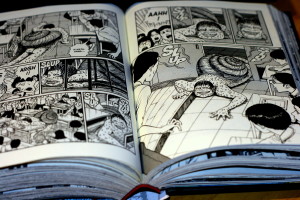

It continues not to be nice. In later stories, school children slowly turn into snails, a girl's hair forms spiral shapes and takes on a life of its own. A boy given to jumping out and surprising people is killed in a car crash, and the suspension spring reanimates his body. It would be daft if the visual intensity didn't carry it, and if Kirie weren't narrating.

Her tone, and the casual acceptance of the townspeople that the weird is ambient are what really sell the uncanny. An enclosure is hastily built in the school grounds for the transformed snail children, for instance, and the residents of Kurouzu-cho take the eventual destruction of the town remarkably in their stride. The extremes ruffle their feathers, but are quickly forgotten in place of little sketches of mundane life amid the horror, and later debris.

So when - in perhaps the most disturbing story - strange mosquito parasites possess patients at a maternity ward, driving expectant mothers to stalk the hospital halls, harvesting blood with hand drills, part of the horror is how calmly it's shrugged off. They attack at night, leaving nurses mystified in the morning. Only Kirie seems to notice. Matter of fact, Kirie ends the tale with: "I've no idea what happened there after that. I wasn't about to go back and find out."

So when - in perhaps the most disturbing story - strange mosquito parasites possess patients at a maternity ward, driving expectant mothers to stalk the hospital halls, harvesting blood with hand drills, part of the horror is how calmly it's shrugged off. They attack at night, leaving nurses mystified in the morning. Only Kirie seems to notice. Matter of fact, Kirie ends the tale with: "I've no idea what happened there after that. I wasn't about to go back and find out."

When Kurouzu-cho itself assumes a final spiral form, its residents congealed into a homogeneous twist of just-aware flesh, the moment has this same almost nonchalance of tone. Ito sets an adventure mystery in the ruins. There's a kind of sleight of hand to around the body horror. It's a feint, and the scares come from the increasingly erratic behaviour of the outsiders who have become trapped there. The fervor one of them brings to describing his desire to eat the snail children raw is as unsettling as the doctor in the maternity ward, as he stitches the parasite mushroom child back into its cadaver-mother.

I wish I were making that up.

I'm not. Uzumaki gets weird fast and stays there. Although its strongest theme is distortion into the spiral (of body, of community, of sanity) it employs a range of techniques to unsettle. Bodily distortion is perhaps the most common theme, and the sheer lack of distortion around these intense squeals of the grotesque is its contrast medium. The townsfolk look on, Kirie describes in her flat, accepting tone, something unfathomable happens, and life continues. Why don't they run? Why aren't they screaming? At risk of mild fatuousness: why don't I close the book?

I'm not. Uzumaki gets weird fast and stays there. Although its strongest theme is distortion into the spiral (of body, of community, of sanity) it employs a range of techniques to unsettle. Bodily distortion is perhaps the most common theme, and the sheer lack of distortion around these intense squeals of the grotesque is its contrast medium. The townsfolk look on, Kirie describes in her flat, accepting tone, something unfathomable happens, and life continues. Why don't they run? Why aren't they screaming? At risk of mild fatuousness: why don't I close the book?

In the end, they can't. As the spiral structure is completed, it drags not just the geography of the town, but the flow of time around its whirlpool. At the centre of the spiral, after we've been given few answers, time stands still. This lap of the cycle is completed when Kirie and Suichi join hands, their bodies twisting together, in the spiral cavern beneath the dragonfly pond.

Uzumaki teases us a little at the end. It evades answers neatly - after all, what explanation could be satisfactory for what we've seen? In the end, the only thing that can tie any of it together is the distorting pull of the spiral.

Should you buy it? Probably, for all that it's a genuinely uncomfortable read. There's some nightmare fuel in the mix there, for sure, and since part of what makes it so interesting is the breadth of techniques it uses to unsettle, you may not get away lightly.

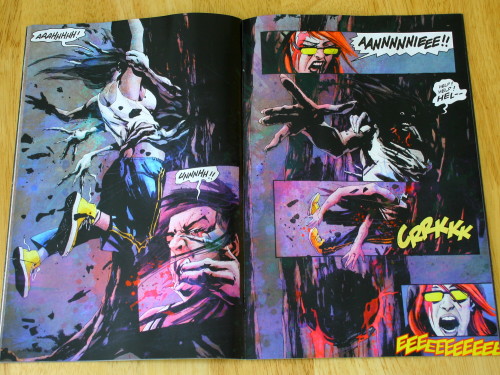

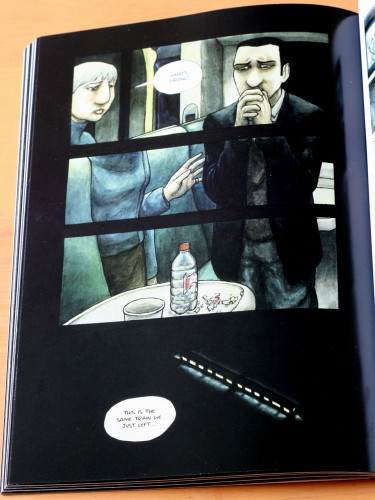

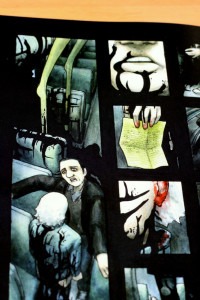

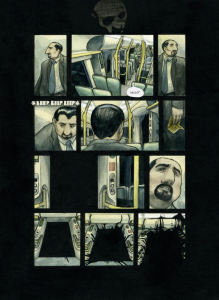

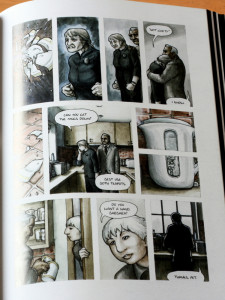

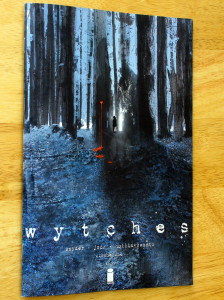

The first issue of Wytches is a striking thing. Part of what I'm thinking of as a current strain of graphic-design-influenced comics, it uses layout and a rich play of digital colouring and texture to create something really quite unusual. It's also heavily infused with a kind of Southern Gothic creepiness, the vibe of small communities and close-pressing forests that is absolutely my narrative catnip.

The first issue of Wytches is a striking thing. Part of what I'm thinking of as a current strain of graphic-design-influenced comics, it uses layout and a rich play of digital colouring and texture to create something really quite unusual. It's also heavily infused with a kind of Southern Gothic creepiness, the vibe of small communities and close-pressing forests that is absolutely my narrative catnip.