Change. How to sum up Change? How about this: Los Angeles will fall, the next Atlantis in a cyclic history, claimed as a great old one rises? Kind of, but that's a bit too phone-it-in Lovecraft. A lone astronaut returns to Earth, dreaming of what he left behind? Technically true, but that sounds like po-faced Oscar-bait sci-fi, and in any case implies too much sense being made. Crazed cultists pursue a screenwriter whose scripts predict the endtimes, and a lost, broken man remembers a past, and the girl he couldn't save? Closer, but too portentous, and lacking the crucial caveat: "but not shit".

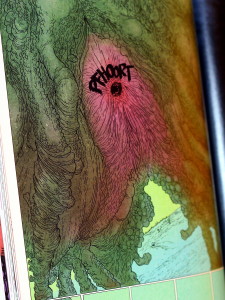

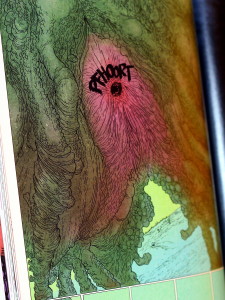

None of that, though, really does justice to quite how chaotic Change is, and none of it touches on the humour. This is a book where the apocalypse is averted with what ambiguously might be a Cthulhu fart joke. This, moments after an aerial surveillance drone achieves sentience, only to crash into a falling space shuttle. It's a book that sticks a playful couple of fingers up at Harry Potter by having a character who looks like a junkie Daniel Radcliffe thwart the Voldemort-alike talking tumour on the back of his head by shoving a foetid sock in its mouth.

None of that, though, really does justice to quite how chaotic Change is, and none of it touches on the humour. This is a book where the apocalypse is averted with what ambiguously might be a Cthulhu fart joke. This, moments after an aerial surveillance drone achieves sentience, only to crash into a falling space shuttle. It's a book that sticks a playful couple of fingers up at Harry Potter by having a character who looks like a junkie Daniel Radcliffe thwart the Voldemort-alike talking tumour on the back of his head by shoving a foetid sock in its mouth.

There's some grimy darkness in Change, and some big emotional punches, and some utterly beautiful artwork and colouring; but there's a lot of fun, too. And not a lot of sense. Or maybe loads - it's hard to tell.

This is a Weird Book. Let's look at that a bit.

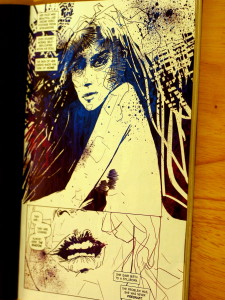

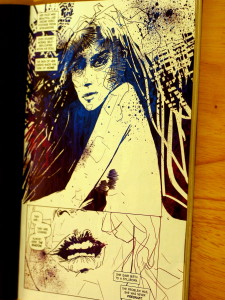

Change opens with a really lovely little fake out that - at risk of over-reading - sets a playful tone for the whole of the book. It's a funky meta joke about the book's own textuality, and I am absolutely going to spoil it for you, right now. The first two pages are dreadful - absolutely fucking awful. Cringe-making, self-involved over-hip tech punk claptrap that go as far as the simile "Her face was beautiful like drone video footage from Afghanistan", all smeared over scratchily fashionable line work that's probably better than what it's parodying. That's just page one.

Overleaf, it dives into lurid mythos-noir-something excesses around a kind of ectopic monster pregnancy, and then your eyes flick over to page three. Colours change, the line settles down, the view pulls out, and we're reading from a script. This is not Change, it's a screenplay written within Change that playfully foreshadows it, and we jump right into an argument about whether it's shit.

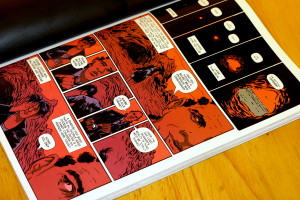

That opening is also a great primer to how Change is going to code things with visual style, especially colour. Sloane Leong is smacking it out of the park here, and there are places where the narrative complexity and chaos would actually feel like bad writing if she weren't. Fast cuts between periods and contexts are made explicit with palette. Saturation rises and falls with the fragility of causality. Simplistically - when it looks super weird, it's super weird with a purpose. But more than that, the colouring really captures the mood.

There's a page towards the end, a final character moment with light washing in through a window from a newly-saved world, that, well, just take a look.

From the establishing joke, it ducks in and out of action, mystic horror, trauma recovery narrative, and borderline-psychedelic nonsense. Screenwriter Sonia Bjornquist and W-2 the rapper and would-be producer she's writing for find themselves on the run from murderous cultists. This (initially) main plot is inter-cut with ambiguous reminiscences from another character - another writer - approaching the narrative on a different trajectory. There's something about trajectories here as a running theme, in fact. Past stories approach convergence in the present, the astronaut approaches the earth, the old one rises. Threads head towards each other form back and front, colliding in a denouement around "Doublehead" - the almost smugly literal central figure. Also, an emotionally broken screenwriter with a deranged apocalypse cultist growing as a tumour on the back of his head.

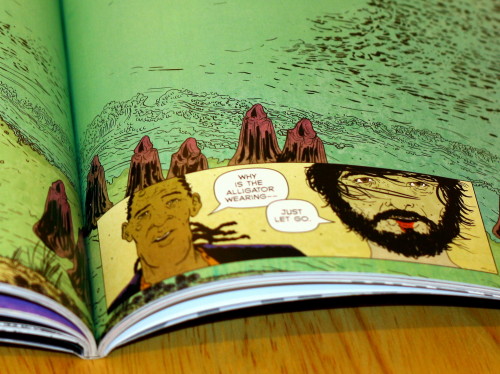

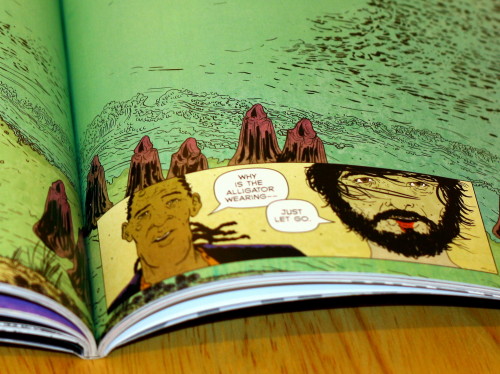

As W-2 and Bjornquist move through a superficially conventional thriller plot, Doublehead drifts through the margins of their story, intersecting at brief moments explicitly as himself, and more solidly as Mr Fissure, the antagonist popping out of the back of his skull. I almost can't believe I just typed that, but it's cool, because the book is in on the joke. It plays with its tropes and conventions, and makes reality malleable to the point of triviality. Certainty and simple causal effects just break down the closer we get to the climax - most visibly where W-2 is faced by an alligator on a beach in a tuxedo, and casually told just not to think about it.

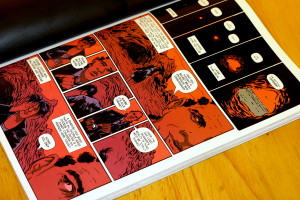

It is shortly after this point that the surveillance drone - which has been zipping about overhead throughout the book - is finally called out by the narrative voice. We're told what it would think, but that it cannot, because "After all, it is a done". Until it can. In poised defiance of the text, the drone achieves self-awareness. Then, suddenly, characters in panels that are spatially and temporally far separated in the narrative - but proximate on the page - seem to talk to each other. The astronaut seems to speak to Doublehead.

Casually, cruelly, and with the same perverse glee as Douglas Adams' plummeting humpback whale, the drone crashes while yelping a delighted "WHEEEEE!!".

Here, too, we've ditched most of the ostensible main plot. The cultists, the chases, W-2 and Bjornquist have basically evaporated. The real story, the one that has been arcing inwards on its symmetrical trajectory with the spacecraft, takes over. Through the chaos the mechanics are well-oiled, for sure. The drone hits the craft. The craft falls. Falling, it scrapes the malign tumour from Doublehead's back - a ludicrous, delicious, loaded coincidence that finally ties off the parallels with his memories and those of the astronaut. The astronaut may be his father, the astronaut may be a version of him; their memories may be identical or merely structurally intertwined. Either way, with the visible totem of his role in the apocalypse gone, Doublehead now has no possible way to avoid dealing with the past he's been trying to write himself out of.

Change's unstable realities coalesce in the belly of the monster. But, again: not shit. It's a weird blend of touching and sinister, as Doublehead more or less forgives himself. Everyone we've met so far would rather fight/instigate and apocalypse than deal with their personal problems, and wedged in the grotesquely, evocatively coloured tract of the great old one, he finally has no choice.

There's a running birth/death association motif, made visual with a repeating birth canal-like, emerging into the light image. We see it again, finally, as the great old one vomits/farts/sneezes him back into the ocean and sinks back into the waves. Reality solidifies. The chaos recedes, and each of our almost protagonists has their own quite little coda.

And that's largely what Change is up to. The apocalypse, and arguably even the idea of linear storytelling, is a backing track for the emotional beats. Doublehead's "I couldn't save you" refrain is mixed in as the inevitable, cyclic apocalypse that structures the ostensible surface plot, itself repeating the theme. The first time we hear it out loud, "I couldn't save you", it's from a middle aged man, dressed like a boy, clutching an antique telephone. We don't yet know who he is, but something here is iconographically up with time, and the words resonate back through the immediate past where nobody could quite save anybody.

I won't claim Change isn't confusing. Its cavalier attitude to its own causality, and the sheer volume of stuff Kot is throwing at us make it downright disorienting. It's not perfect, and there are places where you could argue this goes too far; W-2's hallucinatory timeline jump, for instance. It's neither a comfortable nor a straightforward initial read, and I'll admit there were places where I had no fucking clue what was going on at first. But I do think it's worth it.

It pays off hard if you let it. Just don't worry about why the alligator is wearing a tux.