This week we're giving something back to the people. As Agony Ant-Man, we take listener questions and pump out good advice and comics-related wisdom at a frankly disturbing volume. As in quantity. If it's too loud, turn it down. We can't do everything for you.

We read:

- Manhattan Projects - Jonathan Hickman and Nick Pitarra

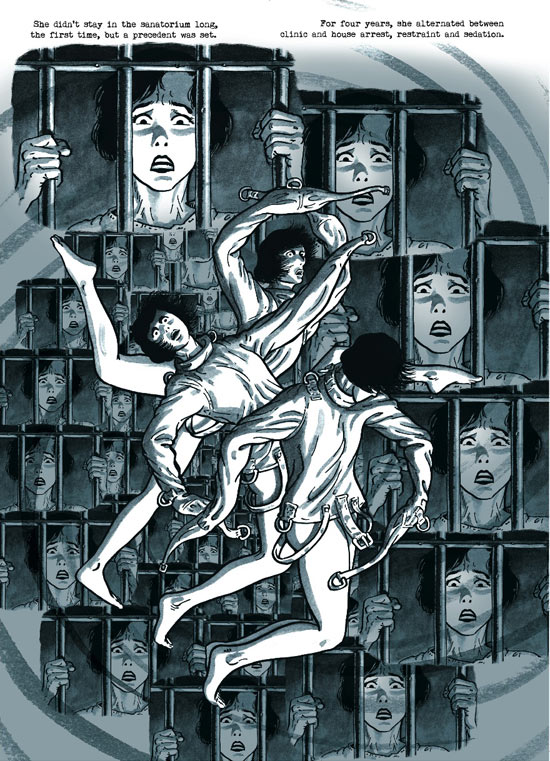

- Stray Bullets - David Lapham

- The Wicked and the Divine - Kieron Gillen, Jamie McKelvie and Matthew Wilson

- Age of Bronze - Eric Shanower

- Terms of Service - Michael Keller & Josh Neufeld

- Ody-C - Matt Fraction and Christian Ward

- Sing No Evil - J. P. Ahonen and K. P. Alare

And to fix your broken and tragic lives, we recommended:

- Atomic Robo - Brian Clevinger and Scott Wegener

- DC: The New Frontier - Darwyn Cooke

- The Unbeatable Squirrel Girl - Ryan North and Erica Henderson

- She-Hulk: either the Dan Slott run or the Charles Soule one

- My Cardboard Life / Soppy - Philippa Rice

- Bandette - Paul Tobin and Coleen Coover

- Chloe Noonan - Marc Ellerby

- Blankets - Craig Thompson

- All-Star Superman - Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely

- Flex Mentallo - Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely

- Joe The Barbarian - Grant Morrison and Sean Murphy

- Asterix - Rene Goscinny and Albert Uderzo

- Rat Queens - Kurtis J. Wiebe and Roc Upchurch

- Kate Beaton

- Stuck Rubber Baby - Howard Cruse

- The Hypo: The Melancholic Young Lincoln - Noah Van Sciver

- Ms. Marvel - G. Willow Wilson and various artists

- I Don't Like My Hair Neat - Julia Scheele

- Double Barrel

- Anything by John Allison

- Will O' The Wisp - Megan Hutchinson and Tom Hammock

- Hildafolk - Luke Pearson

- Everything We Miss - Luke Pearson

- Infinite Vacation - Nick Spencer and Christian Ward

- King Cat - John Porcellino

- The Boxer - Reinhard Kleist

- Mulp - Matt Gibbs & Sara Dunkerton

- Mouseguard - David Petersen

- Journey Into Mystery - Kieron Gillen and Richard Elson

- From Hell - Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell

- League of Extraordinary Gentlemen - Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill

- The Adventures of Luther Arkwright - Bryan Talbot

- Scott Pilgrim - Bryan Lee O'Malley

- Empire State - Jason Shiga

- Age of Apocalypse - Various

- Reading Comics - Douglas Wolk

- Understanding Comics - Scott McCloud

- 1001 Comics You Must Read Before You Die - Paul Gravett, Various

And We Are The Best is based on Never Goodnight by Coco Moodysson. And that NoBrow iPad app is here.